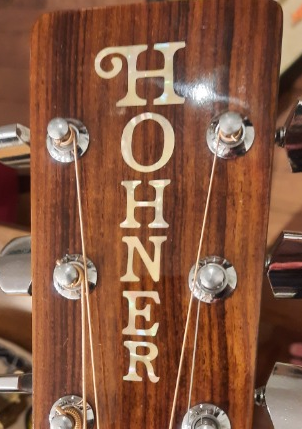

Hohner never settled on a single logo for their guitars in the 50 years they were making them. But there were some that cropped up again and again. Here’s my attempt at a timeline of logos that appeared on headstocks – logos used on soundhole labels, packaging and promotional material will have to wait.

The Berkeley guitars were made for Hohner London, as M. Hohner Ltd styled themselves at the time. Best guess is that they were made in the late 1950s.

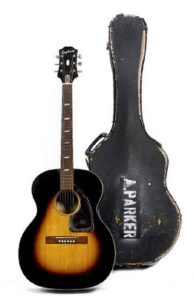

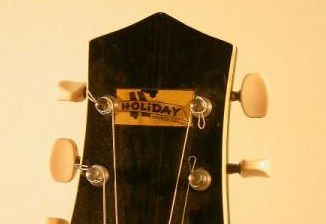

Around 1960, the Holiday archtop guitars were made for Hohner France. It does say Hohner on the headstock but this is the best photo I’ve found.

Around 1961, Hohner London had a series of solid body guitars made for them in England. This is a Zambesi. Other models include Amazon, Apache, Holborn and the Ambasso bass, which all had a similar logo or no maker logo at all.

For a lot of the 1960s and 1970s, no guitars were produced under the Hohner name – the company mostly used Contessa branding for guitars. This is an HG-670 12 string dated towards the end of the 1960s. It was probably made in Germany and the simple block logo is one that’s found on many other Hohner products such as accordions and harmonicas.

In the very late 1960s, the Bartell company made some basses for Hohner USA using this logo.

There are a number of Japanese made Hohners with this logo, usually Telecaster or Stratocaster copies. These could possibly be early 1970s. If they are, these would be the earliest examples of what is sometimes called the ‘teacup handle’ logo. This always has a scroll on the first H and, depending on the headstock shape, an extension or scroll on the R. Later examples were usually a solid colour (or inlay on expensive guitars) but these examples are always gold with a black border.

I’ve seen it suggested that the teacup logo is based on the HS Anderson logo. The guitar above is a 1975 model. HS Anderson is a brand of the Japanese manufacturer Moridaira who at the very least made guitars for Hohner. I suspect it’s a coincidence but it’s certainly an interesting one.

There’s still a lot to discover about what guitars Hohner were producing in the first half of the 1970s. The Contessa range seemed to consist mostly of acoustics, Where Hohner electrics have been dated to pre-1975, there’s usually little supporting evidence or the dating is based on a misinterpretation of a serial number.

One exception is this seemingly very rare Les Paul Custom copy. It’s been dated to around 1974/5 and that is plausible based on the use of the Gibson protected ‘open book’ headstock shape and ‘split diamond’ headstock inlay, which were long gone by 1976 when the better documented era of Hohner guitars started. That makes this the earliest dated appearance of the Hohner script logo which was heavily used for the next few years.

Sometime in the early 1970s, Hohner produced a run of guitars with a wooden ‘movie ticket’ style label under the soundhole which read “Hohner Limited Edition Series 1”. It would make sense for these to have been produced around 1974/5, except for the fact that one owner claims to have an original bill of sale from 1970. In any case, this is probably the first appearance of the vertical ‘teacup handle’ logo which adorned higher end Hohner acoustics and archtops into the 21st century. Known model numbers in Series 1 include the HG-210, HG-220 and HG-230 (not to be confused with later guitars re-using the same model numbers).

Around 1975, Hohner started expanding their range of guitars under the Hohner brand. Amongst the acoustic guitars, the HG-300 series, HG-700 series, and HG-900 series guitars exclusively used the teacup handle logo. The exception is that some HG-320 guitars have the plain logo seen in the middle of the above picture. These could be very early models – dating Hohner acoustics is difficult unless the soundhole label is date stamped, which happens erratically. The other two guitars above are also HG-320 models and you can see that the one on the right has a longer logo extending beyond the tuning pegs.

Some other models outside those series also used the teacup handle logo – HG-26, HG-512, HG-07 and HG-07E.

The remaining acoustic guitars in the range used a script font. Often these were folk guitars rather than dreadnoughts and had been carried over from the Contessa range, which used a similar font and placement for the logo. But there are exceptions. The picture above shows an HG-200, which is a dreadnought but one that had a Contessa equivalent model. Sometimes models that started with a script logo have been seen with the teacup handle logo. Production moved factories and even countries (to Korea) in the life of these guitars and the logo change may be indicative of that.

Hohner also expanded their electric range in the second half of the 1970s. High end models – HG-460, HG-470, HG-480 – got the teacup logo. The HG-800 series (electric archtop) also used the teacup logo.

The most famous Hohner of all is the HG-490. This was a version of the HS Anderson HS-1. The Moridaira factory, who made the HS Anderson guitars, produced a limited quantity for Hohner with their logo. One of those found its way into Prince’s hands and became his favourite guitar. This is a horizontal variation of the teacup handle logo, possibly the first to have the curve and use a large font – a variation that would become more common.

The Les Paul and SG copies in the range used the script logo seen on the contemporary acoustics. Above is an HG-430LP.

The Fender copies used a dark pearloid version of the script logo. This is from an HG-425 Telecaster copy.

This is an HG-455PB bass.

The budget Telecaster-ish HG-420 had a gold with black border version of the script logo.

By the early 1980s, Telecaster and Stratocaster copies were using a bold black version of the teacup handle logo first seen on the HG-490. Above is an MS35 (UK designation). Les Paul and SG copies used the same script logo as before.

In the early 1980s, Moridaira made a through neck guitar and bass for Hohner which had inlaid teacup logos with a concave curve. The IG786 bass version is pictured.

When production of electric guitars moved to Korea, a small number of Stratocaster and Telecaster copies were made with a very small version of the straight horizontal teacup but with a more exaggerated scroll on the R.

When these guitars became the Arbor Series, the logo was retained but made considerably larger.

The Les Paul version of the Arbor series used a similar logo in a different layout.

In 1985, Hohner introduced the Hohner Professional logo, initially for the Korean made B2 headless bass guitar. So technically not a headstock logo as the guitar didn’t have a headstock. This logo was used on the G2/G3 headless guitars and ‘The Jack’ bass which had a more traditional body shape but still no headstock.

The Hohner Professional range soon added many other models. The core of the range for many years were the “ST” Stratocaster type models, the “L” Les Paul type models and the “TE” Telecaster type models. For several years the range also included interestingly shaped and coloured guitars with names like Devil and Heavy, because it was the 1980s.

Early L59 models (up to the late 1980s?) had a very intricate inlay under the logo.

A small side quest

One of the guitars introduced into the Hohner Professional range in 1985 was the TE Prinz. This was a copy of the very rare Hohner HG-490, since made famous by Prince. Hohner made versions of this guitar on and off for the next 25 years.

A reminder of what the 1978-ish original HG-490 looked like.

In 1985, Hohner added the model TE PRINZ to their Professional range. For the next few years, it had the Hohner Professional logo and “The Prinz” on the headstock.

There are at least a couple of these guitars, one owned by Wendy Melvoin formerly of Prince’s band The Revolution, which just have the Hohner Professional logo and at a different angle to the others. It’s not clear if these are the very earliest production models or ones made when Hohner were nervous about Prince’s lawyers.

There’s even one TE PRINZ (or is it?) with an authentic looking body but with a Strat style headstock with this logo. The wavy HOHNER is common on keyboard products and packaging but not often (ever?) seen on guitars.

In the 1990s, Hohner reissued the TE PRINZ but with a different shaped headstock which now actually says TE Prinz.

In 2008, Hohner reissued the Prince guitar again as the HTA-490 Hohner The Artist. The headstock changed shape again but did have a beautiful inlaid logo reminiscent of the original HG-490.

Also in 2008, Hohner sold a limited run of the Hohner The Artist Elite Black Prince guitar, which were made by a Czech luthier.

So there we are, the still not completely understood history of Hohner and Prince told through the medium of headstock logos.

Back to the timeline

Later L59 models had a more basic inlay under the logo.

The B Bass models didn’t have room on the headstock for the full logo so they used an H …

… and put the logo on the body.

Meanwhile, the HMW series of acoustics (and other acoustic models) had started using a gold block logo again. This is an HMW400.

Sometimes they also added “Established in 1857”. This is also an HMW400.

Austrian musician Falco had a signature bass around 1988-91 which had a unique logo.

In the early 1990s, the Revelation series of guitars were developed by a division of Hohner calling itself Hohner Guitar Research. These guitars had the company logo on the truss rod cover.

The logo was often just impressed in black-on-black and was sometimes accompanied by “Guitar Research”.

The SE 400 was a Super Jazzline guitar introduced into the Hohner Professional range in 1992.

Somewhere around 1998, the SE 400 was dropped and the HS 40 introduced. It was basically the same specifications and still called the Super Jazzline but it now had a cursive script logo. The HS 40 went though a few variations after that but the logo stayed the same.

In the late 1990s, the Caribbean Pearl series featured some very blingy finishes and the cursive script logo.

Here’s a slightly more legible (if not any less blingy) logo.

The Classic City series of guitars used the same cursive script logo. This is a Hohner Birmingham.

This is a Reno, The other models were Springfield and Baton Rouge.

The HRB DLX was a 2003 Korean made bass.